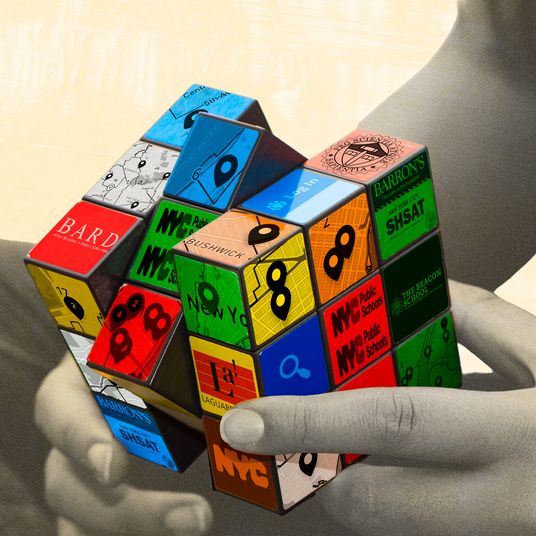

The first day of May has long been one of the most important dates on the college-admissions calendar: the official deadline for high-school seniors to make the big choice of where to enroll the following fall. A decade ago, former First Lady Michelle Obama anointed it “College Signing Day” with a nod to the anticipation around top athletic recruits committing to Division I programs. For both teenagers and colleges, the tradition and expectations were fixed. Schools had already provided all the relevant information for making the decision, and prospective students had a deadline for paying a deposit or surrendering their spot.

That rhythm began to fray in 2020, during the pandemic, when uncertainty pushed decision timelines later. It continued last year with the delayed rollout of a new federal financial-aid form. Many expected 2025 to mark a return to normal. Instead, for reasons ranging from Trump-administration policies to demographics to challenging industry economics, the reality of enrollment day continues to shift. In 2025, a round of last-minute deal-making by some colleges to attract students emerged as a new feature of the admissions landscape.

Zoe, a 17-year-old high-school senior who lives on the East Coast, made her decision this spring thinking that this would be a normal year. On April 29, after weighing admission offers from a dozen colleges, she posted her decision on Instagram for her friends to see: She was headed to the University of Southern California. Although several other colleges had offered her substantial discounts in the form of merit scholarships, the “sizzle and prestige” of USC was too good to pass up, her father, Mark, told me — even if that acceptance came with nothing in financial aid to cover the university’s $96,000 annual price tag with room and board.

But a few days later, before Zoe had declined her acceptances to the other schools that admitted her, an unexpected letter arrived from one of them. Syracuse University offered her a “Personal Distinction Award, in the amount of $80,000, disbursed in increments of $20,000 per year.” Not only did the award surprise Mark and his wife, Claire, for its timing — coming after the May 1 commitment date — but also for its size. Until then, Syracuse hadn’t offered any aid at all toward its $85,000 sticker price, which includes housing and food. “They wouldn’t play ball with us for months but then they dropped a sack of 80 grand on us,” said Mark, whose name, like others in this story, has been changed. “It was like, holy cow, why didn’t this come in 48, 72, or whatever number of hours before?”

The reasons behind Syracuse’s late-breaking offer, and similar actions from other schools, are complicated. The roots go back to 2019, when the National Association for College Admission Counseling, which represents admissions officers and high-school counselors, voted to scrap parts of its ethics code under threat from the Justice Department, which said it stifled competition. A section that discouraged colleges from recruiting students after May 1 was eliminated. (After the vote, one admissions dean posted on the site then known as Twitter: “Welcome to the Wild West.”)

In the ensuing five years, amid the upheavals of COVID and its aftermath, this change wasn’t particularly obvious to prospective students or their families.

The shift in practices this year is partly a result of financial uncertainty imposed on many schools by the Trump administration. Since January, the White House has eliminated hundreds of research grants to colleges and universities, proposed deep cuts in remaining research funding along with the share the schools can take as overhead, and moved to deport hundreds of international students on visas. The administration’s policies have blown a hole in university budgets for the next academic year, leading schools to cut spending and quickly look for new revenue everywhere — even if that means offering last-minute discounts to lure in a few more students who will still pay something in tuition as well as room and board. “Adding another 50 or a hundred students to their class is a nice hedge on many things,” said Brett Schraeder, a vice-president at EAB, an enrollment consulting firm that works with colleges. “They’re making decisions later in the game: ‘Well, maybe we would want another 100 students to shore up some of our bottom line.’”

The other big reason for the change is about demographics and the economic challenges faced by all but the most elite schools. While we tend to talk about college admissions as if it’s a single, uniform process, that isn’t really the case. Top-ranked schools dominate the headlines with their ever-decreasing acceptance rates, but the vast majority of colleges fight for every student they enroll. Undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. reached its peak in 2011 and has steadily declined since then. The percentage of high-school graduates going straight to college hit a high of 70 percent in 2016; by 2022, the last year available, it had dropped to 62 percent.

Basically, colleges across the country are competing for a shrinking pool of students. With the exception of USC, which accepted around 10 percent of applicants this year, Zoe had chosen less selective schools deeper in the rankings. These schools tweak their financial-aid formula almost every year so that they give just enough of a discount on tuition to yield a class. That’s why Zoe’s parents were surprised when she didn’t get any merit aid upfront from Syracuse, which had a 42 percent acceptance rate last year — especially since the school was her top choice early on. Zoe showed that interest by visiting campus, opening emails, and following the university on social media, all things schools track. From the school’s perspective, this made Zoe a strong candidate for merit aid, a powerful tool for convincing students with multiple options to enroll (which, in turn, helps the school’s key stats).

When the late offer from Syracuse arrived, Zoe’s parents were reluctant to discuss it with her. “There’s the mind-set of a 17-year-old kid who announces to the world on social media she’s going to USC, who’s now connecting with roommates and all of that — it’s really hard to undo,” Claire, her mother, told me.

Mark, however, was quick to consider the financial implications. “We’re not ones to look at $80,000 and say, ‘Screw it,’” he added. The couple also knew from Facebook groups that discuss paying for college and a financial consultant they hired to manage the search process that schools were sometimes willing to negotiate. “I told Syracuse that they had to come back with something above and beyond for us to switch,” Mark said. “It was a nervy Hail Mary, but I felt a little burned by Syracuse.” A few hours later, Syracuse added another $10,000 a year to Zoe’s award.

Zoe wasn’t the only one who received a late aid offer from Syracuse, according to parents who posted screenshots of their letters in “Paying for College 101,” a popular Facebook group. Another parent who also received the $80,000 offer from Syracuse, even after they’d declined a spot in the freshman class, told me her son ultimately decided to remain committed to Lafayette College, where he’ll receive a need-based grant of $38,000 for his first year. “He wanted closure,” this mother told me. “He had already moved on from Syracuse.”

A Syracuse spokesman wouldn’t comment on whether the school missed its enrollment target for the fall or if officials were worried about their international enrollment (which makes up nearly 20 percent of the total student body). But the upstate New York institution isn’t alone in poaching students who committed elsewhere by dangling money after May 1. Facebook groups and Reddit threads are filled with stories of last-minute discount offers from the University of Miami, Santa Clara University, and Seton Hall University, among others. Whether they work on families who have already made a decision is another question. One mom said her daughter received a $20,000 merit scholarship at Santa Clara on May 9 — after getting nothing previously — but decided to stay with her original choice, the University of Delaware. “Even with the money, Santa Clara is still more expensive,” the mom said.

The price of college tuition even after discounts has more families weighing the price against the value of the brand name. According to one long-running survey of how Americans pay for college, 81 percent of families with a six-figure income cross a college off their list at some point because of high cost. “There’s maybe a little more pushback this year among the middle- and upper-middle-income families,” said Schraeder, the enrollment consultant. “If I’ve got to pay almost full freight with limited financial aid that may not be worth it to me.”

It appears that this kind of last-minute deal-making will also be the new normal. Starting in 2026, the number of high-school graduates is projected to steadily erode throughout the next decade. “We’re now moving into the age of survival of the fittest, where revenue trumps ethics,” said Angel Pérez, CEO of NACAC. “The majority of our members want to do good for students, but if campuses don’t meet their goals, it means existential questions about surviving.”

In the case of Zoe, at least, it worked. On May 13, about two weeks after committing to USC, she told Syracuse she was in. “Don’t judge me too harshly,” Mark said. “I work in sales. I know these are businesses. But this is silly season.”

The next wave of parents is already taking notes. In Facebook groups, they’re tracking which colleges offer 11th-hour discounts, preparing to outlast admissions offices next year. “It’s a dangerous game,” warns Schraeder, as institutional fortunes can shift rapidly. Yet Schraeder told me that EAB’s surveys confirm what Zoe’s family discovered firsthand: The college search has fundamentally shifted from “I’m going to the best school I get into” to a more pragmatic calculation — “the best school that gives me the most money.” In today’s admissions landscape, an $80,000 (or more) surprise is simply too valuable to dismiss, even after the Instagram announcement has been posted.