Labour once treated the Greens with magisterial indifference. A party with two leaders and not many more MPs was rarely deemed worthy of attention. But in recent months that’s started to change. Darren Jones has accused them of “offering simple solutions to complex problems”, Steve Reed has called them “wacky” and, mining Zack Polanski’s hypnotherapist past, Rachel Reeves has warned that the only things that would get bigger under him are the deficit and inflation.

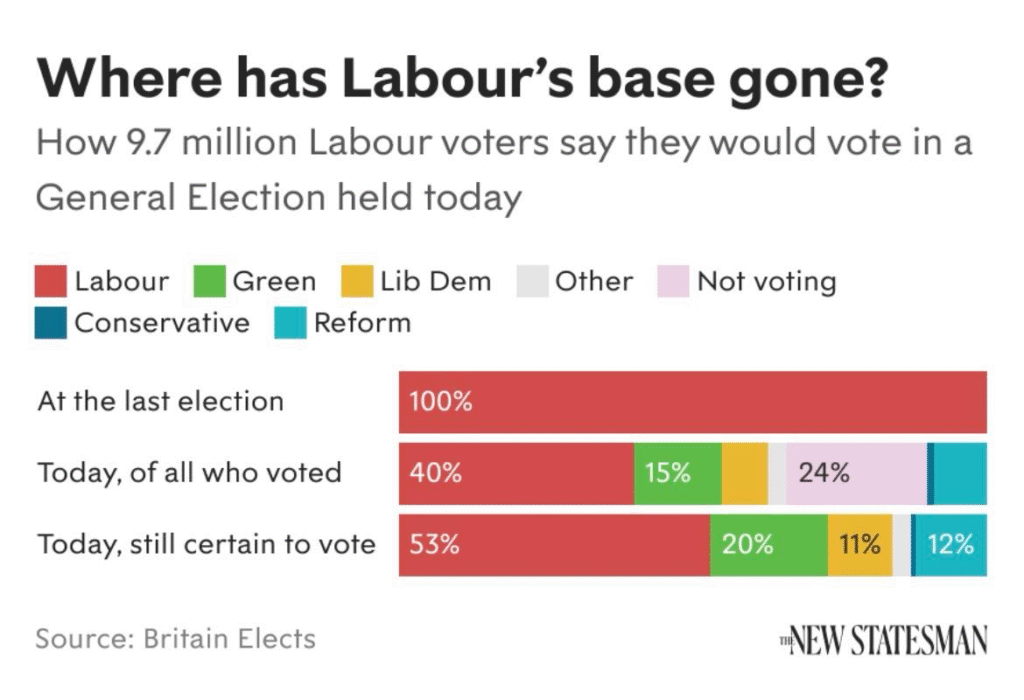

There’s a simple reason for this proliferation of attacks: the Greens have surged. Having polled around 10 per cent before Polanski’s election, the party now averages 14 per cent, not far behind Labour on 18 per cent. The crucial detail, as Morning Call has long noted, is that the Greens are now claiming 20 per cent of Keir Starmer’s 2024 voters, comfortably ahead of Reform on 12 per cent and the Lib Dems on 11 per cent. In an election today, our polling guru Ben Walker estimates, they would win 23 seats and finish a close second in 31 others.

So it’s unsurprising that Starmer himself has joined the fray. “They’re anti-Nato at a time when the world is more volatile than it has ever been,” he told the Observer in an interview published yesterday. “The Green Party thinks it’s all right to sell drugs and there should be no restrictions. So somebody could sell drugs outside my children’s school but, if you’re a landlord, it should be unlawful. That’s nuts. They’re dangerous.”

Starmer did alight on several vulnerabilities for the Greens. Just 17 per cent of voters trust them on defence (compared to 54 per cent who trust them on the environment). In an era when war has returned to the European mainland, an anti-Nato stance is a distinct risk among progressives as well as conservatives (Polanski now insists that he does not favour withdrawal until an “alternative alliance” has been formed). Similarly, only 4 per cent of voters back the Greens’ policy of drugs legalisation.

But Starmer’s answer also provided further evidence of why Labour is struggling. As one government source laments, rather than offering “values arguments designed to appeal to the type of people interested in the Greens”, it simply listed “two unpopular policy positions”.

It’s not as if Labour doesn’t have a record capable of appealing to Green-curious voters: it has championed net zero under Ed Miliband and imposed a ban on new North Sea oil and gas licences; it has passed a Renters’ Rights Act ending no-fault evictions and a rail public ownership bill; it has raised taxes on “private equity, private schools and private jets” (as Reeves recently put it); and it has suspended 30 arms licences to Israel and recognised a Palestinian state.

Wes Streeting’s response to Polanski’s comments on social care workers – “I don’t particularly want to wipe someone’s bum,” he told Question Time – was notably stronger because it questioned the Greens’ progressive credentials and class consciousness. “Social care is a hard, rewarding, skilled professional job,” said Streeting. “That’s why we’re delivering the first-ever fair pay agreement in social care and building a care profession”.

This is the terrain on which Labour can challenge Polanski. Dismissing them as “nuts” won’t work – if you’re responsive to that charge you’re unlikely to be the kind of person who would ever consider voting Green. But arguing that Labour is a more genuinely progressive choice might. And if that doesn’t, warning that a divided left vote will put Nigel Farage in No 10 is a decent reserve option.

Almost 20 years ago, deploying much the same tone as Starmer, David Cameron dismissed an insurgent Ukip as “fruitcakes” and “loonies”. How did that one go? The risk for Labour is that, unless something changes, Starmer’s attack is remembered as no less effective.

This piece first appeared in the Morning Call newsletter; receive it every morning by subscribing on Substack here

[Further reading: The economics behind Zack Polanski’s claims]