On his third day shooting Heated Rivalry, Jackson Parrell found himself lighting a Russian funeral in the dining room of an Italian restaurant in Hamilton, Ontario. The room was dim. A dozen mourners sat shoulder to shoulder, their faces caught in the low glow of table lamps. “I was like, fuck,” Parrell says. “This is one of the best scenes I’ve ever had the opportunity to light.”

When he signed on as cinematographer of the now-viral hockey romance, Parrell worried the series would “look Canadian,” industry shorthand for “visibly underfunded.” Months earlier, at a dinner party in Toronto, Jacob Tierney, a friend of a friend, mentioned a project he was developing for Crave: a drama about rival hockey captains who fall in love, adapted from Rachel Reid’s Game Changers novels. It would be explicit. It would move between Montreal, Moscow, and Vegas. There would be penthouses and arenas, banquets and hotel suites. “It’s probably the lowest-budget thing I’ve ever shot,” says Parrell, whose credits include North of North and Anne With an E. Not quite “five dollars and a dream,” but negligible by HBO standards, where Heated Rivalry streams Stateside. “I won’t say I did it as a favor,” he tells me. “But for a minute, I thought it might be a family affair.”

The schedule, as laid out, was punishing: just over a month to shoot, at 10 to 11 pages a day. (On North of North, Parrell shoots four or five.) The hockey didn’t help. A single line of action — Shane passes and gets bodychecked — could take up half a day once stunts were involved. Even so, Tierney had a reputation. Everyone Parrell knew who’d worked with him on Letterkenny said the same thing: He was fast, and he was really, really good. Parrell was skeptical. “I was like, This is the furthest thing from Letterkenny,” he says. “I’ll believe it when I see it.”

On most shows, Parrell shoots a lot more than he needs, anticipating changes and network notes in post. On Heated Rivalry, Tierney had full creative control. “Jacob knows exactly what he wants, and he doesn’t want anything beyond that,” Parrell says. “He’s not trying to cover his ass.” Elsewhere, a two-person scene might take three hours; with Tierney, it took 45 minutes. Some days, they even wrapped early. Tierney gave Parrell free rein over the show’s visual language, from lighting to color to composition. “Jacob and executive producer Brendan Brady would say, ‘Just do what feels right,’” Parrell says. “It’s like they wrote me a blank check, creatively.” The same attitude carried across the set. “Everyone was allowed to sing at full volume. It was a fucking joy.” The crew had one rule: Nothing onscreen could feel like a giveaway of the budget. “It’s about playing to your strengths,” Parrell says. “You gotta let people cook a little when you don’t have a lot of money.”

The basics: “We wanted it to feel cinematic, even with our budget.”

Parrell hopes you’ll overanalyze his use of color. Heated Rivalry’s palette tracks the story: Shane Hollander (Hudson Williams) and Ilya Rozanov’s (Connor Storrie) romance begins in dark hotel rooms and gradually moves into the light, a progression baked into both Tierney’s script and Reid’s novel. The rest is taste. “I wanted everything to look beautiful all the time,” Parrell says. With colorist Maxime Taimiot, he developed the show’s “full-fat” look — rich, saturated images that resist the muddy, flat aesthetic he associates with larger studio fare. “That’s not how I want to live,” he says.

Parrell shot Heated Rivalry with two ALEXA 35s, high-end digital cameras built for low-light shooting. “That alone bought us a lot of scale,” he says. “We wanted it to feel cinematic, even with our budget.” But the show’s look really came from the lenses. Parrell opted for Panavision’s T-Series anamorphics, which stretch the image into a wide, movie-style frame and allow for extreme close-ups. “It’s low-hanging fruit,” he says. “An easy way to instantly elevate the show.”

Hockey scenes are expensive — crowds especially — and Heated Rivalry couldn’t afford to fill stadiums with background actors. So Parrell and Tierney cut the hockey down to the bare minimum, shooting it in a broadcast style that kept the stands out of frame and allowed the footage to look worse on purpose. They shot the action at a higher frame rate, using large zoom lenses to mimic the crisp, artificial feel of live sports coverage. Onscreen, these scenes appear as a smaller image boxed inside the wider frame. “The hockey had to be subservient to the show’s larger world,” Parrell says.

Since Heated Rivalry couldn’t afford to film in key locations — including Las Vegas, Sochi, and Tampa — Parrell re-created them with a VFX wall, a massive digital screen used to generate three-dimensional environments. He worked with the Toronto-based company Dark Slope, using the video-game software Unreal Engine to design the backdrops. “It can go very wrong very fast,” he says. “The uncanny-valley risk is high.” An outdoor café scene in “Olympians,” for instance, never quite worked. “I just couldn’t, for the life of me, get the Sochi street to look realistic.” Parrell asked production designer Aidan Leroux to build an ice-cream-and-coffee shop and moved the scene indoors, making the VFX wall the view outside — the same trick they used to create the Vegas skyline in the pilot, “Rookies.” “That really solved a lot of problems.”

Still, the wall had its limits. Parrell couldn’t get the water texture to look right for the beach scene in episode five, “I’ll Believe in Anything,” where Shane watches the sunset with Ilya. “If you use the VFX wall as a singular thing, it falls apart,” he says. “You need a little piece of foreground, like a coffee cup or something shiny, just to bring the viewer back into the world.” To build back the realism, the crew created a narrow sand berm in front of the screen, disguising its edge. “That scene was risky,” Parrell says. “But sometimes you just have to lean into it and hope it looks good.”

The Vegas bathroom: “You can see the soul through that little light.”

During an awards ceremony in Vegas, Shane and Ilya duck into a bathroom to argue, then make plans to see each other later that night. For Parrell, this confrontation in episode two, “Olympians,” was as simple as it gets: “Two guys walk in, they stand close together, and we get some nice shots of them.” Parrell kept the setup minimal: one light, maybe two, “enough to get something in their eyes.” They shot the scene with a single camera and let the actors work.

The technical term for that “little sparkle” in Williams and Storrie’s eyes is eye light. “It sounds ridiculous,” Parrell says, “but I feel like you can see the soul through that little light. For me, it’s almost a path to empathy with the character.” He heightened the effect with two filters: Tiffen’s Black Glimmerglass, which softened the image and took the “crispy edge” off, and a polarizer, which stripped away most of the sheen from the actors’ skin. “It makes Connor and Hudson look really present,” Parrell says. “Once that shine is gone, you’re pulled straight to their gaze. Now the only thing sparkling is these boys’ eyes.”

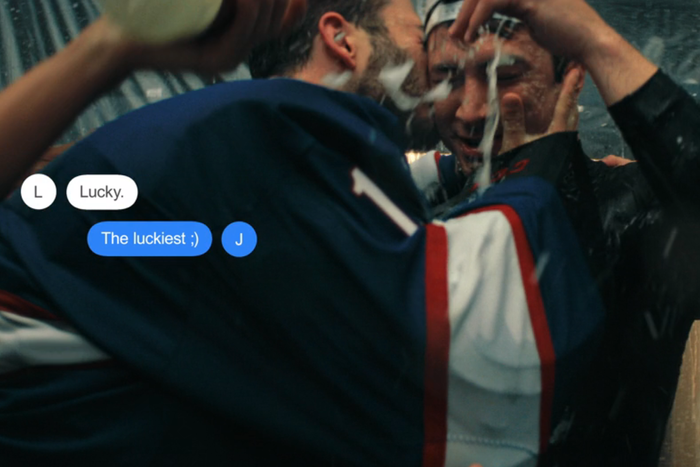

The Champagne celebration: “It smelled insane for days.”

In episode four, “Rose,” the Metros celebrate winning the cup with a locker-room Champagne shower. “We didn’t actually tell Hudson we were gonna spray him with Champagne,” Parrell says. Just before rolling, Tierney leaned over and whispered to a few of the actors, “Start spraying him in the face.” They only had time for one take, so Williams’s reaction is “completely genuine,” Parrell says. “He didn’t know any of it was gonna happen.”

To protect the gear, Arthur Moukhortov, the show’s on-set dresser, wrapped the cameras, operators, and the locker room inside the Sleeman Centre, a Guelph arena where the series shot all its hockey scenes, in plastic. They shot the scene in slow motion, with Moukhortov playing Soren Miitka, the bearded player who kisses Shane on the cheek. Afterward, Moukhortov stayed behind to clean up, sweeping puddles of “Champagne” from the floor. “Can you imagine covering an entire room in Welch’s sparkling grape juice?” Parrell says. “It smelled insane for days.”

The club: “You’ll know exactly where you are just by the color.”

Parrell organized each episode into “color chapters” with a distinct visual identity. “It’s like a fingerprint,” he says. “Line up every frame, and you’ll know exactly where you are just by the color.” Shane’s scenes with his girlfriend, Rose (Sophie Nélisse), for instance, are deliberately “very golden,” while the club sequence in episode four leans into the familiar “bisexual lighting” trope. It almost seemed too obvious — Shane and Ilya under pink, purple, and blue strobes, dancing with other people and staring at each other across the floor. “It was just the best look I could come up with,” Parrell says. “These colors look great together. There’s a reason they’re so heavily used.”

The club scene builds toward a risky wraparound shot. When Ilya spots Rose’s friend Miles (Devante Senior) at the bar, he realizes Shane must be nearby. The camera tracks Ilya’s eyeline as he scans the room. “We had very little coverage here,” Parrell says. “If the wraparound didn’t work in the edit, we’d have nothing else to cut to.” Later, the movement reverses: Shane clocks Ilya and starts walking toward him, the camera moving so that “we’re orbiting with Hudson as he comes around Connor.” Parrell shot the sequence in slow motion, at 60 frames per second, and then ramped it in post, stretching the moment as t.A.T.u.’s “All The Things She Said” slips into its remix.

The final montage cuts between Shane and Ilya watching each other on the dance floor, Shane having sex with Rose, and Ilya alone in the shower. Parrell pushes the camera so close to Williams and Storrie’s eyelines that it nearly breaks the fourth wall. “If you’re going to do that, you have to mean it,” he says. He wanted the moment to feel like a rupture — “like something went off” — and timed a strobing flash to hit at the emotional peak. The rest came down to the cuts. “It was important for them to feel really intentional and close,” he says. “You’re always trying to connect Shane and Ilya in those moments, to build that yearning between them.”

Ilya’s monologue: “It almost feels like they’re in the same room.”

After his father’s funeral, Ilya finally tells Shane everything he’s been holding back — over the phone, in Russian. The scene was meant to be shot in an industrial stretch of Hamilton, but when the location fell through, Parrell and Tierney found something better: a public tunnel painted entirely pink. “When a location gives you something like that, you say thank you and work with it,” Parrell says.

To fake winter in Moscow, the special-effects department filled the tunnel with artificial snow. Parrell gave Storrie a few places he could “stop and look great,” then let him freewheel. Storrie paced and then sat, snow blowing around him, as camera operator James Poremba followed with a handheld. “That was a long one for James,” Parrell says. “We rolled on that whole thing as a single take.”

The scene cuts between Ilya in Moscow and Shane, on the road for a game, listening from a hotel stairwell. Ilya’s close-up is dim; Shane’s is cooler, more exposed. “They’re in completely different time zones,” Parrell says. “I wanted to feel that contrast.” But their eyelines match, their faces angled toward each other across the cut. “So even though they’re on opposite sides of the world,” he adds, “it almost feels like they’re in the same room, talking to each other.”

The Scott-Kip kiss: “This shot is the show.”

In the final moments of episode five, Shane and Ilya’s fellow hockey star, Scott Hunter (François Arnaud), becomes Major League Hockey’s first openly gay player after kissing his boyfriend, Kip Grady (Robbie G.K.), on the ice at Madison Square Garden. Parrell says he cried when he read the script. “I was like, this shot is the show.” To do it justice, something else had to give; half of the show’s VFX budget went to episode five, and most of it was spent on the kiss. “No one misses the hockey stuff they didn’t see,” Parrell says. “But everyone remembers the kiss. This is the screenshot for the internet.”

The kiss itself was shot in an empty studio. Parrell worked with the VFX company FOLKS, using 3-D LiDAR scans of the Sleeman Centre to build a digital version of Madison Square Garden, extending it row by row. “VFX make or break a scene like this,” Parrell says. “We really couldn’t have anything look fake.” To create the crowd, the crew spent a full day at the arena, shooting part of the crew and about 50 background actors in different outfits and team colors cheering, booing, standing, sitting, and eating popcorn. FOLKS turned the footage into a modular library of real bodies that could be duplicated and viewed from any angle, then populated the stands. “If you really dig deep,” Parrell says, “you’ll eventually spot the same person twice.”

The cottage: “I always want these guys to be in the same frame.”

After Scott comes out publicly, Ilya decides to join Shane at his remote cottage, where they can finally be alone together. Parrell says Tierney described episode six, “The Cottage,” as a honeymoon for Shane and Ilya. “‘I always want these guys to be in the same frame,’” Parrell remembers him saying. “‘Why would we give them single shots and make people feel any distance between them? This is who they are in this space.’”

In fact, the only time Shane and Ilya appear apart at the cottage is when they’re sitting on the couch and Shane reacts to Ilya suggesting he could marry his childhood friend, Svetlana (Ksenia Daniela Kharlamova), for citizenship. Even then, Parrell says, they’re not really apart. “They’ve been touching toes the whole time. There’s always a little string between them. We’re just trying to build the love between them, and show it everywhere we can.”

The cottage scenes came together so quickly that production actually got ahead of schedule. One afternoon, Parrell noticed the light changing over the lake. Earlier that day, they’d filmed a scene with Shane and Ilya sitting side by side on a rock, watching the sun go down. The real sunset was better. “I was like, ‘Guys, let’s reshoot it,’” he says. “No shows have that flexibility, ever. But we’re such an efficient team that we got everyone back in their wardrobe and shot the scene again. And it’s gorgeous.”

The blowjob: “This is what the people want.”

At the cottage, Shane takes a call from his teammate Hayden (Callan Potter) and stays on the phone while Ilya goes down on him. The framing is suggestive without being too explicit — a balance Parrell credits to his camera operators, Ashley Iris Gill and James Poremba, who worked closely with Tierney, Williams, Storrie, and intimacy coordinator Chala Hunter to find the right angles for the scene. “Sometimes, you can tell people are a little shy with sex scenes,” Parrell says. “James and Ashley got it. They knew exactly what we were here to do.” Before filming began, Parrell gave them one directive: Throw away everything you’ve ever thought about the male gaze. “This is the one time of your life you’ll be completely liberated of any cultural stigma around it,” he told them. “Lean into it. You can get the edge of the frame, just above the modesty garment, every time. This is what the people want.”

Once Shane hangs up the phone, he hops over the couch and onto Ilya, and the scene becomes what Parrell calls “nose-to-nose intimacy.” “I’m always trying to build those moments in,” he says, “especially with Ilya’s necklace moving in the sex scenes.” For him, shots like this matter as much as the sex itself. “They build true, close intimacy,” he says, “in a way that lets you take it all in at once.”

The foot taps: “I knew there would be memes.”

During a joint press conference in the premiere — shot with bright, flashing lights to suggest a crowd just out of frame — a reporter asks Ilya a question he doesn’t understand. Shane nudges Ilya’s foot to signal he can step in; Ilya nudges him back in thanks. The gesture needed to feel covert, so Parrell broke it off as a dedicated shot. That gesture returns in “The Cottage,” when Shane and Ilya sit opposite Shane’s parents at their kitchen table after coming out. Parrell pulled up the original frame from “Rookies,” trying to match it. “I knew there would be memes,” he says — “or I hoped there would be.” The first image is dark and cool; the second is soft and sunlit. The contrast was intuitive. In the pilot, Shane and Ilya are still near strangers. “But that second scene — that’s the point of the show,” Parrell says. “They get a happy ending. Of course the light should be warm.”

The credits: “This is a happy love story, and it can be yours.”

Heated Rivalry ends with Shane and Ilya driving back to the cottage. The scene was filmed on a VFX wall, which meant Parrell had to find a background plate that could do two jobs at once: sell the illusion of a scenic drive and last long enough to carry the show’s full end credits. Most series cut away well before every name appears. Tierney was adamant about letting them run uninterrupted in order to build the crew into the show’s final image. “Jacob designed the shot assuming people would stay and watch it,” Parrell says. “It’s a really nice nod.”

Onscreen, late-afternoon light flickers across Shane and Ilya’s faces, as if filtering through trees along the road. To create the effect, Parrell worked with head lighting technician Loreen Ruddock and lighting-board operator Claire Wall, programming the “sun” to respond to a strip of pixels marking where the trees would pass, flashing on and off in real time as the car moved. “If the sun is too perfect, then you know it’s fake,” he says. Parrell wanted it to look real — the exact golden hour when Shane and Ilya would be driving home. “I just wanted it to feel aspirational,” Parrell says. “This is the queer story where there’s no gotcha moment. This is the shot where we hit that home run. This is a happy love story, and it can be yours.”

More ‘Heated Rivalry’

- Agents Are Looking for the Next Heated Rivalry on Fanfic Sites

- Gus Kenworthy Wouldn’t Mind Meeting Heated Rivalry in the Rink

- Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie Heat Up the Olympic Torch